RAVENNA 1312-21

by R.M. Corbin

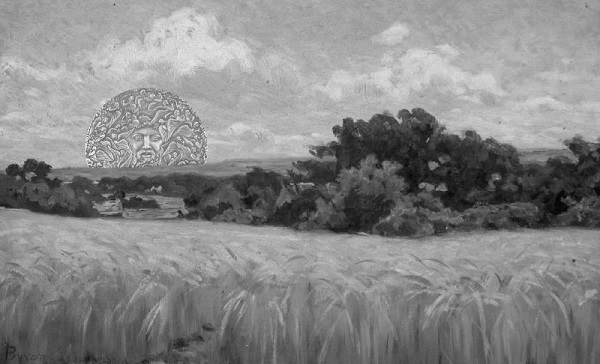

Borso had barley tea at dawn then headed out into the barley fields to reap and heap his

proverbial daily bread of which he' d only get the proverbial heel. He muttered a litany to a lamb.

He walked with his scythe held in his left hand and slung over his left shoulder because he' d lost

his right arm to Guelph cannonfire. No color matters but one's own red. Dante watched from a

high window and nodded along with Borso's weary hobble. He watched him take the scythe in

his one hand and move to his knees—almost in prayer—then shuffle forward, swinging his scythe

and levelling the barley. He watched this half-man reap the fields. He almost heard a click. He

took to his desk and wrote of Purgatorio's fifth terrace, placed a Pope there and made him sing

Adhaesit pavimento anima mea, then forgot about Borso the barley reaper.

Dante died. His son, Iacopo, also a poet, found the last pages of Paradiso under his father's bed

and completed the Comedy that would have the Alighieri name carved in stone and bound in the

national tongue. After Mussolini died, his soldiers led a suicide mission to die atop Dante's

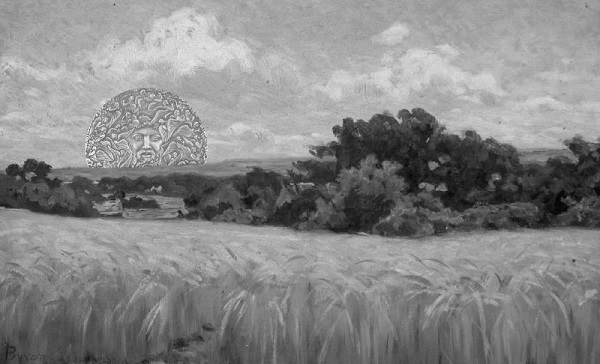

bones. None remembered Borso, but nevertheless laid in the dust like the penitent barley as the

reaper's scythe grew near.

Borso died. His sons buried him in the barley in the hopes that it would poison the landlord.

These sons could not read but their sons could a little and the sons that followed even a little

more. A son—more belated—eventually read the Comedy. He preferred Joyce but Joyce preferred

Dante. When he arrived at the penitent avaricious he was struck by the beauty of the sway of

their shoulders in the dust and at once felt himself there besides Dante but also besides

something else that he could only describe as beautiful and strange. He never found the words

for it.